Post-AGI, you'll need a Rabbi

Self-actualization and a role for religious/communal professionals in a post-AGI world

From 1986 to 1992, thousands of people lined up each Sunday outside a Tudor brownstone in Crown Heights, Brooklyn—the headquarters of the Chasidic Chabad movement—to receive a single dollar and a blessing from its leader, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. While he intended these dollars to be an encouragement to give charity, for many of his followers, it was a deeply meaningful opportunity for personal connection with and inspiration from their Rebbe; many kept these dollars1 as a memento, commemorating a brief, precious shared moment and blessing. As Rebbe, he embodied and transmitted a spiritual dynasty stretching back to 18th century Russia; the movement’s foundational texts draw from kabbalistic works from 16th century Galilee and 13th century Spain, as well as the Babylonian Talmud (compiled between the 3rd and 6th century), itself a compendium of oral teachings spanning hundreds of years that, by tradition, originated alongside the giving of the written Torah at Mt. Sinai around 1300 BCE.

Last fall, I attended the bar mitzvah reception for the son of a local Chabad rabbi (let’s call him Rabbi Shimon). During his toast, Rabbi Shimon gave his son a dollar that Shimon received from the Rebbe in 1990 (on a date, hand-written on the dollar, that 20 years later coincidentally became the bar mitzvah boy’s birthday). Rabbi Shimon then read a letter that he personally received from the Rebbe (a prodigious correspondent) in the 80’s commemorating the occasion of Shimon’s bar mitzvah, reiterating the message as if it were being delivered to his own son today.

This rite of passage was dripping with meaning, infusing countless layers of religious ideals, historical significance, personal blessings, and inheritance into an object as mundane as an old dollar bill. I envision the bar mitzvah boy, 25 years from now, reaching into the dark depths of a drawer to retrieve that dollar—a talisman2 of his heritage, imbued with the blessings of a spiritual tradition spanning four continents and over 3000 years—and adding yet another layer when he passes this worn piece of paper to his own son.

***

I was drowning in dread within days of starting my first job as a tech transactions lawyer in 2011, at a big-name Big Law firm in New York. I’d spent three years gunning through high-pressure law school exams, writing hundreds of pages of my own class outlines, all in the hope that it would carry me to a prestigious, important, high-impact career. But I’d suddenly found myself scrolling through a data room with hundreds of contracts to review for an M&A deal, overcome with the sense of having deeply, deeply fucked up. The old joke they used to tell us as young associates was that working at a law firm was like a pie eating contest where the award is more pie; the endless strings of words to process and manipulate would come with significant financial rewards, but also just more and more words. Vyvanse and cigarette breaks and Spotify playlists and big late nights out all helped me cope, but my mental health and relationships were suffering.

I was fortunate to find a path out of that job in 2013, first relocating to San Francisco for a smaller firm, later moving in-house to Google in 2015, and gradually transitioned to a more balanced relationship to work. But I soon found myself staring down that same old sense of dread; the dissociated feeling that I was just manipulating symbols in word documents, fulfilling socially-constructed legal and commercial conventions. It started to feel like my contracts, rather than being engines of technological progress, were just descriptions of a force of nature;3 that technological progress (if not these specific deals), in some shape or form, would proceed one way or another and that the words I was manipulating to describe it were essentially inconsequential.4 As Alan Watts once observed, “the menu is not the meal.” All this very deliberate computer touching began to feel meaningless to me.

It’s now 2024, and while we’re still torturing highly-paid young lawyers with endless strings of words (for now…), the tech/business/creative world has drawn its collective attention toward the process of feeding endless strings of words to virtual brains (a.k.a. “training large language models”) and marveling over their output. If you’re paying attention to AI, that output seems to be getting noticeably better every few months.

Elon Musk recently reiterated his position that “probably none of us will have a job” in a near-future AGI5 scenario. He elaborated:

“…there will be universal high income. Not universal basic income, universal high income. There will be no shortage of goods or services. And I think the benign scenario is the most likely scenario. Probably, I don’t know, 80% likely, in my opinion. The question will not be one of lacking goods or services. Everyone will have access to as much in the way of goods and services as they would like. The question will really be one of meaning. If the computer and the robots can do everything better than you, then does your life have meaning? That’s really what will be the question in the benign scenario.”

(emphasis mine)

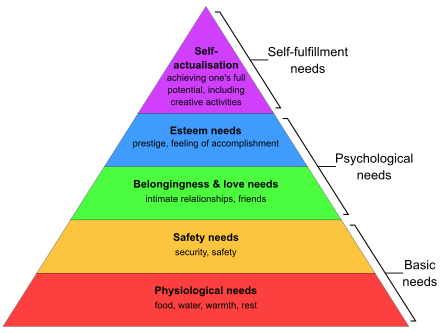

If he’s right,6 this would be a very good problem to have. To a techno-optimist like Elon, AGI will drive humanity up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, with an increasingly large percentage of individuals having their physiological and safety needs met, leaving only psychological and self-actualization needs to be filled.

There’s another big assumption lurking within Elon’s statement, conflating a lack of job with a lack of meaning. Certainly, many people derive meaning from sources aside from work. When Pew explored this question in 2021, it appeared that “Family and children” was the top-cited source of meaning, but “Occupation and career” was in fact a close second alongside a dozen other factors.

It’s easy to understand why work takes such a high spot. Work not only helps financially support family, pay for material well-being, and provide a source of community, but also provides a venue for “a sense of accomplishment and personal growth” (as noted by the Pew study), the self-actualization-peak of Maslow’s hierarchy. For a person who finds their work to be among the top-3 meaning-giving factors in their life, losing their job to AGI would actually be a step down the pyramid, even if their material needs were otherwise met. In this world, nearly everyone would have their basic needs met, but perhaps fewer would have the opportunity for self-actualization, a sort of ontological compression for humanity.

So to refine and restate the question posed by Elon: in a world that no longer needs your labor but otherwise satisfies your material needs, how would you find self-actualization?

I had the good fortune, years ago, of having lost that sense of meaning and purpose in my old career for reasons that have nothing to do with AI. This disenchantment created an opening for a desire to move beyond workism; not only to find deeper meaning in family and community, but most importantly, the possibility of self-actualization outside of work. For me, that’s largely taken shape in the complex of obligations and possibility of growth spanning my individual, familial, and communal practice as a Jew. What really moves me, what I believe is really lasting and enduring and important for me in this world, has less to do with my economic value and output, and more to do with the role I play in an epic story that spans and transcends space and time.7

I suspect that many more will go through a similar sort of crisis of meaning after losing their work to AGI. And if that’s the case, then a core task for civilization in the coming decades will be to find ways of conferring meaning and self-actualization outside of work.

I believe that religious and communal professionals will help guide us down that path.

To return to Rabbi Shimon—his religious belief permeates his family and community life (particularly given that it's also his profession), creating meaningful experiences for himself and his community. It’s a demanding way of life, with thousands of prohibitions, obligations, and customs, but his religious practice generates countless purposeful commitments, each carrying potentially transcendent significance, embodying the fulfillment of his life’s purpose and reaching toward the infinite.8 As a rabbi, Shimon has the specific knowledge9 of how to embody and create meaningful experiences, albeit for the subset of Jews with whom his specific approach resonates.

Shimon is a religious leader. To be sure, religion ranked poorly as a source of meaning among the 17 advanced economies that were covered by the Pew poll. But I’d argue that the low ranking makes it low-hanging fruit for many to explore (among the many other non-work sources of meaning cited); and just as discussed above with respect to work, many religious practices can help reinforce other sources of meaning, such as family, community, mental health, and education.10 But other communal leaders, like political activists, educators, or musicians could also help fill this need. The key skill, I think, will be helping individuals find purpose, self-actualization, and transcendence outside of work.

When AGI comes, the Shimons of the world will probably be fine. I do not think there will be an API call to replace prayer or create meaningful, real-world communal experiences. To the contrary, we’ll be looking to Rabbi Shimon and other communal leaders to help fill the gap in meaning that will emerge for many in their post-work reality. If you’re currently staking your sense of meaning and self-actualization on work, consider, if only as a hedge, finding your own Shimon (or Shimon-like approach to life).

Thank you

and for your feedback!My understanding is that most people would keep the dollar bill and then use different currency to give to charity.

I can’t shake the concept of the Technium, as articulated by Kevin Kelly, which paints the progress of technology in inevitable, near-organic terms. See more here: https://www.perplexity.ai/page/What-Is-the-6zYYmKdnTMaPP2oWWF64kw

Important disclaimer: contracts are, in fact, important. I’ve always prided myself on doing quality work and take my ethical obligations as a lawyer seriously. But I’ve also told many of my clients that I see contract drafting and negotiation primarily as a vehicle for important and clarifying conversations about hard topics. The ideal, nearly everyone agrees, is that after the contract is signed, that it’s filed away and never looked at again (which in and of itself can make the drafting/negotiating exercise a bit kafkaesque). The menu is not the meal.

Artificial General Intelligence. Ilya Sutskever, former chief scientist at OpenAI (whose mission is to eventually build AGI systems), gave a fairly vague definition on stage at TED: a system that can be taught to do anything a human can be taught to do. But OpenAI has itself used a less-demanding definition in the past, defining AGI as a system that surpasses human capabilities in a majority of economically valuable tasks. What this will probably look like in practice isn’t a single, all-powerful entity in the sky—instead it’ll probably look more like boring cloud software-as-a-service, spinning up the equivalent of millions or billions of college or graduate-level virtual workers on demand via API for pennies on the dollar. Imagine being one of the 700 customer service agents made redundant by Klarna’s recent move to replace its customer service function with AI.

It’s a big “if” but I think he’s directionally accurate. You can find a vivid elucidation of this possible AGI-driven future in

‘s excellent summary of Leopold Aschenbrenner’s paper Situational Awareness. To be sure, a more measured, contrarian take can be found from here.“We can see life as a succession of moments spent, like coins, in return for pleasures of various kinds. Or we can see our life as though it were a letter of the alphabet. A letter on its own has no meaning, yet when letters are joined to others they make a word, words combine with others to make a sentence, sentences connect to make a paragraph, and paragraphs join to make a story... I am a Jew because, knowing the story of my people, I hear their call to write the next chapter. I did not come from nowhere; I have a past, and if any past commands anyone, this past commands me. I am a Jew because only if I remain a Jew will the story of a hundred generations live on in me. I continue their journey because, having come this far, I may not let it and them fail. I cannot be the missing letter in the scroll. I can give no simpler answer, nor do I know of a more powerful one.” Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, A Letter in The Scroll

“The rabbinic elaboration of the covenantal vision offered Jews an all-embracing way of life, a system of actions and symbols touching upon nearly every aspect of human experience…. A large range of immediately relevant experiences enabled Jews to feel that their present lives had significance and a sacred purpose.” David Hartman, A Living Covenant: The Innovative Spirit in Traditional Judaism

As used by Naval Ravikant, “specific knowledge” is uniquely precious and valuable knowledge, often the result of human experience. See https://www.perplexity.ai/page/What-Is-Specific-sjNlJczbQbmpOZW6laCw2g

Relatedly, Yuval Noah Harari made a similar observation, calling Israel’s religious community “the most successful experiment so far in how to live a contented life in a post-work world.” See https://apple.news/AYAucwXVVQSS1mMf9QJkdgg

I love your take on looking at that Pew stat on what gives peoples' lives meaning and seeing the lower % categories as low hanging fruit. Jobs and families tend to take up a lot of time and many of the other categories tend to be happening on the side (if people have family). It's exciting to think about the possibility of what our culture would be like if people were able -- either by AI or by re-prioritization of time -- to put more energy into religion, pets, friends, hobbies. AI or not, that feels like a good prescription for a more meaningful life. Thank you for your research and your musings, David!

The world (Jewish and non-Jewish) is lucky to have your vision, commitment, and wisdom.