This post was inspired by a presentation I gave to my rabbinic preparatory cohort after we completed our study of Mishnah Berakhot, an early foundational text of rabbinic Judaism.

***

What if the secret to sustaining a civilization for thousands of years could be distilled into a carefully crafted prompt?

When people use metaphors to explain the world, they often resort to the ascendant technology of the era.1 Enlightenment-era writers likened the universe to a clockwork mechanism, intricately and yet deterministically guiding the movement of heavenly bodies with precision. In the 20th century, as computers became prevalent, some began to see reality as a complex information processing system; the internet provided yet another new metaphor for interconnectedness and global consciousness.

In our era, generative AI chatbots like Claude or ChatGPT readily demonstrate the generative power of language. In truth, this is one of the oldest assertions in Western theology—the biblical tradition tells us that G-d uttered “Let there be light” and prompted the world into existence. Even in everyday practice, the most generic Jewish blessing over food invokes G-d as the one “through whose word all things came into being.” This principle courses throughout the Jewish tradition, asserting that language contains unfathomable power to create, affect, and even sustain reality itself.2

What is new in our time, I think, is an increasingly palpable sense of this power; that short, simple combinations of words can contain tremendous amounts of creative potential, encoding complex and yet ordered outcomes.

I believe that our contemporary encounter with generative AI vivifies these old insights in the Jewish tradition. Moreover, our increasingly generative relationship with language sheds light on how Torah, and perhaps all canonical texts, function as a font for creative discourse.

This was my big takeaway from my first foray into the study of the Mishnah: the Mishnah is a prompt for generating a vital spiritual and ethical tradition. Just as a tiny seed contains the genetic blueprint and creative potential for an entire tree, the concise language of the Mishnah provides the germ for generating vast possibilities for Jewish thought and practice. And I’d like to suggest that the sages who wrote the Mishnah intentionally harnessed this generative potential through a unique economy of language, storing the potential energy for Jewish civilization to survive, regenerate, and unfold3 over centuries of exile.

Economy of Language

The Mishnah was compiled around 100-300 CE, only a generation or two removed from the cataclysmic destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem at the hands of Rome in 70 CE. Alongside the traditional written corpus of law and scripture that existed at that time—essentially the Old Testament, or Written Torah—Jewish sages had, for over 1000 years prior, passed along an oral tradition transmitting innumerable legal, ethical, and spiritual debates/rulings/stories known as the Oral Torah. With the loss of Jewish sovereignty in Judea, and the urgent need to preserve Jewish tradition in the face of Roman domination and dispersion, Jewish sages decided to commit this oral tradition to writing in the form of the Mishnah. The Mishnah is the earliest, foundational layer of rabbinic texts that is today known as the Talmud.

Mishnah Berakhot—one of 63 sections or “tractates” of the Mishnah—is meant to contain vital information about daily blessings and prayers, but contains only about 2000 words. It’s pithy, but in a totally idiosyncratic way. It’s not a code of law; it rarely makes clear, definable statements of what is or isn’t permitted or normative. Instead, it often resorts to strange, incredibly specific, almost koan-like scenarios:

"If one was reciting the Torah, and the time for the recitation of the Shema4 arrived—if he focused his mind, he has fulfilled it, but if not, he has not fulfilled it." (Mishnah Berakhot 2:1)

"Workers may recite the Shema at the top of a tree or on top of a course of stones—what they are not permitted to do with the Amida5 prayer." (Mishnah Berakhot 2:4)

As a lawyer, it initially struck me as odd that an infamously legalistic tradition would indulge in cryptic, terse hypotheticals and stories, rather than make clear, crisp statements of the law in what was intended to be a civilization-sustaining text.

Early in my legal career, I learned about “economy of language,” the principle of using as few words as possible to achieve one’s aims. In contrast to what is known as "legalese"—obtuse, long-winded, difficult to understand—”economy of language” argues that clear, concise, and precise legal writing actually functions better and helps prevent misinterpretation. Contracts should use plain English that a 10-year-old could understand, as opposed to long-winded, hard to parse legalese: for example, "Tenant will pay $1000/mo in rent" instead of "the Tenant hereby covenants and agrees, in consideration for the demised premises described herein…" (etc.).

In the context of an oral tradition, you could see how economy of language might develop naturally. In theory, straightforward, easily memorizable statements would be more transmissible at fidelity over time.6 Assuming the written Mishnah has at least some basic fidelity to the original oral tradition, you would expect to see some examples of economy of language that serve the fidelity of the oral tradition.

Here, the language seems economical—2000 words!—but it doesn’t seem to be optimizing for clarity. Instead, it appears to be optimizing for generative potential.

Encoding Discourse

Let’s take the second example above, "Workers may recite the Shema at the top of a tree or on top of a course of stones--what they are not permitted to do with the Amida prayer." (Mishnah Berakhot 2:4). The original thirteen Hebrew words of this Mishnah (each individual section of the tractate is confusingly referred to as a “Mishnah”) address a fairly esoteric yet important topic, namely the particular state of mind required in order to fulfill a religious obligation to recite a specific passage of Torah. Directly describing this particular state of mind would be extremely difficult to articulate in the abstract, and in all likelihood would still require verbose demonstrations by way of example. The more economical approach taken by the Mishnah is to implicitly embed numerous elucidating follow-on conversations and debates in the text. In this case, we have a seemingly bizarre example that nevertheless encodes at least three different “hooks” for further deliberation, much of which is captured in later portions of the Talmud and its commentaries:

"Workers" prompts discussion in the Gemara7 distinguishing them from a typical homeowner; the “worker” in this case would be accustomed to working in a tree or on top of a wall, and could have a level of subjective comfort and ability to focus in that situation. In other words, the ability to attain the necessary state of mind may vary based on a person’s life circumstances and experience. Someone less familiar with being in those locations would be distracted and therefore need to step down in order to be able to recite the Shema.

One could also read "course of stones" as directing the Gemara to further distinguish certain ineligible types of trees permitted to the workers for this purpose, highlighting the need to be able to stand upright or be in a position of real or felt physical stability as a requirement for attaining the appropriate state of mind.8

"…not permitted with the Amida prayer" establishes a gradation in intent that, due to the differences in the purpose and subject matter between the two prayers, can shed light on the different states of mind required by way of comparison.9

So these 13 words, rather than optimizing for clarity or simplicity, instead prompt these follow-on debates which, over time, clarify the fundamental principles.

But the purpose of this discourse isn’t simply to elucidate the basic rules; the discourse is in and of itself a vital part of Jewish civilization! The generations of rabbis and students who followed the Mishnah, and debated and turned over its cryptic and terse language (in some cases recording these debates and adding additional layers to the written corpus of texts) themselves participated in this generative process of creating and sustaining Jewish civilization. And even today, anyone who engages with the text, discusses it with a friend or teacher, or has the chutzpah to write about it online, further sustains this ongoing creative process. By cryptically condensing this creative potential into the Mishnah, its redactors infused its words with generative power that prompts Jewish discourse to this day.

***

This lens on canonical texts—as generative prompts for culture-creating discourse—isn’t exclusively Jewish. For example, the 45 words of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (protecting the freedom of religion, speech, separation of church and state, etc.) has itself been cited and debated in hundreds of court cases, refining the parameters of its application and further defining these foundational sensibilities within American culture.

Like America’s founding fathers or the redactors of the Mishnah, we can craft foundational documents for organizations or projects with an eye towards their generative, deliberative potential, particularly those that we wish to have real staying power. It can be safe—or even culturally productive!—to be cryptically terse, approaching the task as if we’re prompting our successors’ discourse.10

The chatbot metaphor demonstrates how our creative engagement with texts is an essential and vital outgrowth of those texts; that our resulting words and actions are meaningful output prompted by the text; that we are all potential standard-bearers connected in an endless chain of creative meaning-making.

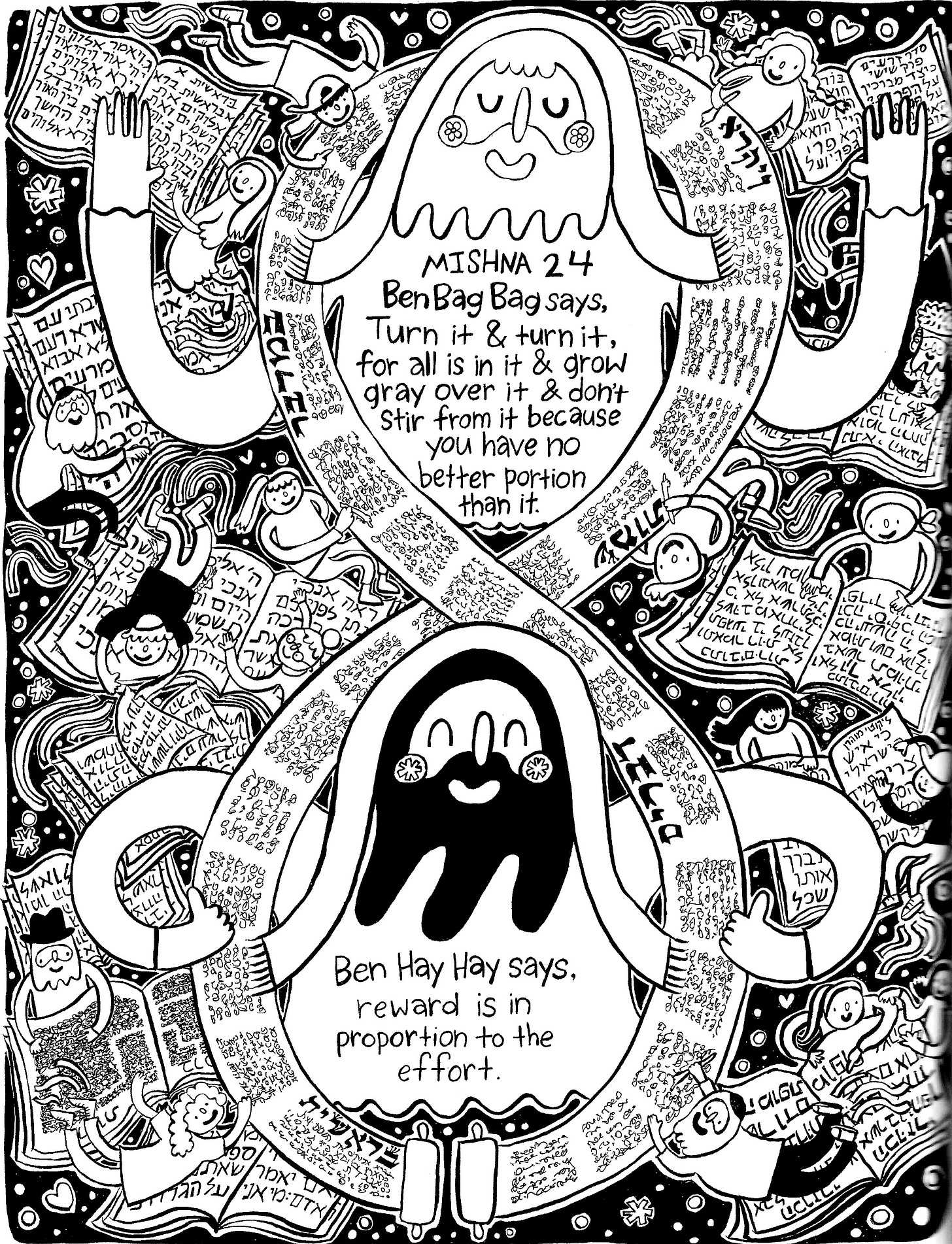

I believe that Judaism (and its foundational texts) has distinguished itself in this respect. It is radically accessible, fundamentally participatory, and therefore endlessly generative. In a different tractate of Mishnah, Pirkei Avot, a sage named Ben Bag Bag teaches “Turn it and turn it, for all is in it….”

For example: (1) One of the oldest works of the Kabbalah, Sefer Yetzirah, asserts that G-d created the world using the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet (later vividly illustrated 1000 years later in the story of the Golem); (2) In the Chabad chassidic tradition, these letters even sustain reality itself: “For if the creative letters were to depart even for an instant, G-d forbid, and return to their source, that source being the degree of G-dliness from whence they emanate, all the heavens would become naught and absolute nothingness, and it would be as though they had never existed at all, exactly as before the utterance, ‘Let there be a firmament’” (Tanya, Sha’ar HaYichud 1:3); (3) The Talmud regards speaking ill of others (the sin of “lashon hara” or “evil speech”) as containing the literal power to destroy the speaker, the subject, and the listener. (Arakhin 15b)

Hat tip to

for sharing this thought provoking piece. In a tweet from June, he reflects on the iterative, organic process of his own personal development mirroring what Christopher Alexander calls an “unfolding” in the linked piece. I’m pointing to a similar, fractal quality here (also suggested by the cellular automata image above) where layer upon layer of Jewish culture “unfolds” in a dynamic process shaped by, and fundamentally connected to, the generative power of the foundational layer of words in the Mishnah.A twice-daily obligation to recite a specific passage of Torah.

A longer prayer recited three or four times a day, intended to replace the sacrifices that were previously offered at the Temple in Jerusalem.

In fact, memorizing and quietly repeating words of the Mishnah is an extremely old tradition that persists in religious communities today, a possible holdover from the ancient practice of oral transmission and memorization that pre-dated the Mishnah’s redaction. Being easily memorizable would have remained important even after the redaction of the written Mishnah, given that it would be another 1300+ years before the printing press would make written volumes more accessible.

See Berakhot 16a:9. The Gemara is the second “layer” of the Talmud, a commentary on the Mishnah compiled around 500 CE.

See Berakhot 16a:9; Koren Talmud Bavli also cites the Jerusalem Talmud on this point.

This state of mind required for the Amida is later vividly described in Mishnah Berakhot 5:1: “Even if a king greets him, he must not respond [while he is praying]; even if a snake is wound around his heel, he must not interrupt [the Amida prayer].” See also, e.g., Bartenura on Mishnah Berakhot 2:4

Appropriately enough, you could probably use AI to do this—e.g., “rewrite and summarize this into a single, simple sentence or two, optimizing for generative and discursive potential.”

This prompted a lot of thinking ;) 🙏

🪝 I particularly like the “hooks” concept as an intentional feature woven into the condensation project needed to transform the enormous surface area of the Oral Torah to something just over 200,000 words.

It works thematically with the prompt analogy but also pedagogically for this inexperienced learner and civilization-sustainer that appreciates attachment points for future expounding, clarification and interpretation 🧗.

Kol Hakavod